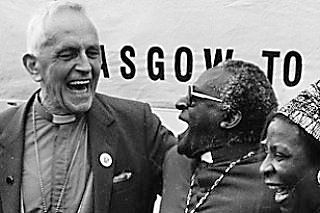

Trevor Huddleston and Desmond Tutu

By Roland Ashby

As we limp, COVID-weary, into the New Year, fearful of what the future may hold, the little flame of hope for humanity and the planet still flickers – but only just.

Feeling bereft of that bright beacon of hope, joy and compassion – Desmond Tutu – our world seems a little darker now one of the great lights has gone out.

Tutu was a giant who stood on another giant’s shoulders – English Anglican priest Trevor Huddleston, who lived and served in the slums of Johannesburg in South Africa in the 1940s and 50s. Nelson Mandela said of him that no white man did more for South Africa.

For Tutu, meeting Huddleston at the age of nine and witnessing the way he treated his mother, a cook in a women’s hospital, was a dramatic turning point in his life, and one which led to his own selfless and transformative ministry.

Tutu recalls:

I was standing with [my mother] on the hostel veranda when this tall white man, in a flowing black cassock, swept past. He doffed his hat to my mother in greeting. I was quite taken aback; a white man raising his hat to a black woman! Such things did not happen in real life. I learned much later that the man was Father Trevor Huddleston.[1]

This moved Tutu so powerfully because it was much more than just a simple act of kindness and respect, it was the embodiment of Christianity’s radical core belief that all of us, regardless of status, ethnicity, disability, gender or sexual orientation, are made in the image and likeness of God. Each of us is a child of God and loved by God. We all have the spark of divinity in us! This is a profound and revolutionary belief that can move mountains if it is lived out, as Huddleston did, and Tutu would do later.

Indeed, it is this core belief, so courageously witnessed to by Huddleston and Tutu, that would help to remove the apparently unmovable mountain of Apartheid – the objectification of others as inferior and not worthy of respect.

Objectifying others is a function of our everyday dualistic minds which judge, measure, and separate in simple binaries like black/white, right/wrong, win/lose – and which can also trap us in cycles of fear, racism, ostracism and violence.

Both Tutu and Huddleston, however, as men of deep prayer and contemplation, brought a contemplative mind to their relationships and their understanding of the world.

What is the contemplative mind? It is a deep spring of love, joy and peace which flows in each of us, enabling us to see with what St Augustine described as “the eye of the heart, whereby God may be seen”. Jesus called this deep spring “Living Water” with which we will never thirst. (See John 4:10-14)

“The contemplative mind refuses to objectify”, Franciscan priest Richard Rohr says. “It grants similarity, subject to subject relationship, likeness ... communion, connection, meaning.”[2]

We connect with the contemplative mind when we meditate, and enter what Benedictine monk John Main described as “the stream of love that flows constantly between Jesus and his Father. This stream of love is the Holy Spirit.”[3]

For Trappist monk Thomas Merton, it was his deep connection to the contemplative mind that could enable him to write:

I have the immense joy of being a member of a race in which God became incarnate. As if the sorrows and stupidities of the human condition could overwhelm me, now I realise what we all are. And if only everybody could realise this! But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun.

It was as if I suddenly saw the secret beauty of their hearts, the depths of their hearts where neither sin nor desire nor self-knowledge can reach, the core of their reality, the person that each one is in God’s eyes. If only they could all see themselves as they really are. If only we could see each other that way all the time. There would be no more war, no more hatred, no more cruelty, no more greed.[4]

___________________________________________________

Forgiveness, and Jesus’ injunction to “love your enemies” (Luke 6:27) were also at the heart of Desmond Tutu’s faith and prophetic ministry. Bishop Philip Huggins, President of the National Council of Churches in Australia, and three other authors, have produced a Lenten study for 2022 on the theme of forgiveness. See https://cdn.csu.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/3944378/2-FINAL-Forgiveness-A-Study-Guide-E-book.pdf

Roland Ashby also leads online sessions in Christian meditation. Email editor@thelivingwater.com.au for more information.

[1] Cited by Andrew McGowan on page 305 of his tribute to Trevor Huddleston ‘A Christian warrior against Apartheid’ in Heroes of the Faith – 55 men and women whose lives have proclaimed Christ and inspired the faith of others (Garratt Publishing, 2015)

[2] From Richard Rohr’s daily meditation for 12/1/22. See https://cac.org/daily-meditations/explore/

[3] Cited on page 83 of John Main – Essential Writings, selected by Laurence Freeman (Orbis Books, 2002)

[4] Cited on page 52 of A Book of Hours by Thomas Merton, edited by Kathleen Deignan (Sorin Books, 2007)