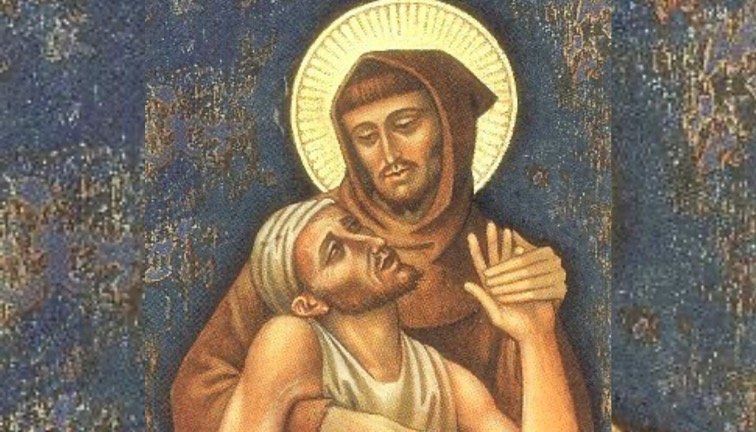

St Francis of Assisi embracing the leper.

Suffering, for many, is one of the greatest stumbling blocks to faith. But for the Christian mystics, it is a way of entering into the suffering of Christ and transforming our attitude to the suffering of others. Roland Ashby reflects.

As I look back on 2022, I had my own share of suffering, which included five stays in hospital.

With Job, I wanted to cry out “Why?” Why do I have to suffer like this? Andrew Mayes expresses this well: “Job’s ‘why?’ is the timeless question that surfaces in a million hearts today. Why do children die through warfare? Why do innocent people perish through ‘natural disaster’? Why am I suffering with this illness right now? Where’s the sense in it?”[1]

In seeking solace and meaning, I have found it helpful to turn to the mystics.

St Francis of Assisi (c.1181-1226) and 14th century mystic Julian of Norwich were both well acquainted with suffering.

Mayes writes: “Francis’s whole life was marked by the experience of suffering, hardship and debilitating illness. He looked on these experiences as a way of uniting himself with Jesus Christ, whom he understood as God’s love and compassion incarnate.”[2]

Moreover, St Francis became so united with Christ he even entered into Christ’s suffering on the cross, through receiving the stigmata.

And by embracing suffering, his attitude to the suffering of others was transformed. A turning point came when he met a leper. Mayes writes: “Normally, he recoiled at the sight of the disfigured and disabled sufferers. In fact, he had an absolute horror of them ... But something stirred within his heart when he met this tortured man ... He felt impelled ... not only to approach the man, but to touch him tenderly, to embrace him. Later, he wondered if had not met Christ himself in this encounter.”[3]

Julian of Norwich’s faith was also completely transformed by an encounter with Christ in the midst of her own intense suffering, when she received a vision of him on the cross. “At the same time as I saw the bleeding head, our good Lord gave me a spiritual vision of his simple loving,” she writes.[4] She continues, in what is a beautiful and moving image of the way Christ loves us, by comparing it to something as simple and ordinary as our clothing and shelter: “I saw that he is everything that is good for us, everything that sooths and helps us. He is our clothing; he wraps himself around us, enfolding us in his love. His tender love is our shelter; he will never leave us.”[5]

This vision goes on to reveal, when she was shown “a small thing, the size of a hazelnut”, representing the whole of creation, that creation only exists through the love of God, and God is its “creator, lover and sustainer”.[6]

Even though suffering and sin she is told are a “necessary” part of the creation, these do not have the last word, and she is assured that “We are his divine treasure, and he holds us in such profound love here on earth that he will give us more light, solace, and joy in the world-to-come, drawing our hearts from the sorrow and darkness in which we are now living.”[7]

It is an image of God consistent with the one that Jesus presents in the Prodigal Son. Not a punishing, vengeful God, but one who eagerly awaits our “return home”, joyfully running towards us so as to embrace us with an extravagant, even ‘prodigal’ love.

During my hospital stays, I experienced the incarnational love that St Francis and Julian of Norwich reveal through their lives and writing. Just as Francis was Christ for the leper, so my paramedics, nurses and doctors were Christ for me.

Through them, even though I suspect not many would have identified as Christian, I believe God’s love was breaking through into the world. Like Job, I was indeed discovering that “God is bigger than all our categories of him”.[8]

And in my times of contemplative prayer, and meditation on Scripture, I also experienced God’s love as something as real and tangible as being wrapped around me like clothing or shelter, as Julian describes.

This was particularly true for me when I reflected on two gospel passages: Mark 10:13-16, and Mark 10:17-21.

In the first passage, where Jesus invites the little children to come to him despite his disciples’ disapproval, and where he “took the children in his arms, put his hands on them and blessed them”, I imagined myself as one of the young children, and simply rested in Christ’s arms, delighting in Christ’s love and blessing. This was a time of great peace and healing for me.

Likewise, in the second passage, where Jesus meets the Rich Young Man in search of what he must do to find eternal life, I imagined myself as the young man, and for a long time stayed with this one line, “Jesus looked at him and loved him”, perhaps one of the most beautiful in the gospel, but one we tend to skip over. I allowed myself time to simply soak up that loving gaze, and be held in it; and indeed to be wrapped in it. To do so is to experience in a very tangible way the treasure of heaven that Jesus holds out to the young man in the next verse, and to understand why “sell everything you have” in order to enter such a heaven is not as shocking as it seems.

Meister Eckhart (c.1260-c.1328), and the 14th century mystical text, The Cloud of Unknowing, written by an anonymous author, also offer us a wellspring of wisdom.

Eckhart believed that God was to be found in all creation, and that through silence, stillness and letting go of self, and all thought, including our concepts and images of God, our eyes would be opened to seeing God in all things, and that God is at work in everything that happens.

This includes experiences of suffering. “The way of letting go invites us to let go of the present impact of these experiences and allow God’s grace and healing to bring us to a new sense of freedom,” John Stewart says[9].

In the letting go, and the emptying out of self in contemplative prayer, God is reborn in us, Eckhart believed, and this also enables us to see the suffering of others through God’s eyes. Thus, Stewart says, compassion becomes our response to the suffering of the world.

One of the sources of The Cloud of Unknowing is 6th century Greek theologian and philosopher Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, who is key to understanding the book. As Cath Connelly says: “His theme is that we can experience a union with God only by unknowing.” This is because, she adds, “We are not capable of comprehending God with our minds”, and as The Cloud says, “You cannot think your way to God; you can only love your way to God”.[10]

How does this help us with suffering? By embracing the mystery, and by risking the vulnerability of letting go of certainty, the need to know, and also power and control over your situation; and by being willing to transcend, go beyond self, thought, doubt and fear, and allow yourself to fall into the arms of the God who is Love.

The way to do this, The Cloud says, is by repeating a mantra, “in the fullness of spirit” and with “a sharp dart of longing love”.

In our day, both the Centering Prayer Movement and the World Community for Christian Meditation continue in this tradition.

I also meditate in this tradition, and have found that my fears and doubts dissolve, my mental anguish and suffering is calmed, and, as I learn to let go of all thoughts and give complete attention to the mantra, the experience becomes one of being held in love. In this state, I have also found that joy and peace naturally arise, as well as compassion for others, and thus in the words of The Cloud, “The contemplative does not ‘see’ God; the contemplative enters into God’s seeing”.

By being attentive to the mantra I find that, in the words of Thomas Merton, I experience “the happiness of being at one with everything in that hidden ground of Love for which there can be no explanations”.[11]

This is a great source of healing too, because I find myself being more able to accept sorrow and suffering as part of life, and that in the mystery of this “hidden ground of Love” sorrow and suffering can be transformed.

But this is not to deny the reality of the sorrow and suffering. As author and priest Sarah Bachelard says, while we are born into a world of wonder and delight, it is also a world of threat. “There’s the sheer risk of embodiment and of living in a physical universe, in a mortal frame, and the suffering and danger that comes from that.”[12]

But God does not leave us on our own, she says. While God does not rescue us from “the terrifying risk of embodied life”, he does come to share it:

God does not cancel the threat but comes to empower us to be in the midst of it in a particular way – in a way that remains open to possibility and deep listening, that continues to love in the face of fear and unimaginable loss, that calls us to be with and for one another and ourselves, redeeming and transforming suffering by undergoing it truthfully, our wounds becoming sacred wounds – portals to grace.[13]

Footnotes:

[1]Andrew D. Mayes, Spirituality of Struggle: Pathways to Growth, 40

[2] Ibid., 43

[3] Ibid., 43

[4] Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love, translated by Mirabai Starr (Canterbury Press 2014) 13

[5] Ibid., 13

[6] Ibid., 13

[7] Ibid., 224

[8] Andrew D. Mayes, Spirituality of Struggle: Pathways to Growth, 41

[9] Heroes of the Faith – 55 men and women whose lives have proclaimed Christ and inspired the faith of others, edited by Roland Ashby (Garratt Publishing 2015) 217

[10] From a talk given as part of a course on spiritual direction at The Living Well Centre for Christian Spirituality. See http://www.livingwellcentre.org.au/

[11] Thomas Mertion, A Book of Hours, Edited by Kathleen Deignan (Sorin Books, 2007) 59

[12] From a sermon given at Benedictus Contemplative Church on 31 December 2022. See https://benedictus.com.au/

[13] Ibid.